“The First Perfusionist I Ever Met” By Gary Grist RN CCP Retired

The first perfusionist I ever met was a guy named Jerry Swett. In 1968 when I was 19 years old and after a year of being a hospital orderly (and going to college classes around my work schedule), I started looking for a better paying and less physically taxing job. An ad in the newspaper was looking for a “Special Technical Services (STS) Technician” at the same hospital. It paid twice what I was getting as an orderly ($2.10/hr vs $1.07/hr). I had no idea what a Special Technical Services Technician was, but the ad did not say that experience was necessary. So I applied. My interview was with a former medical technician named Shirley Melton, who was the head of this new hospital department. She only asked me two questions. Firstly how did I feel about working for a woman? Since I had just spent a year taking orders from floor nurses and received good reviews from them, I did not think it would be an issue. Secondly she showed me something I had never seen before. It was a stainless steel manifold comprised of 5 linked stopcocks. She asked me to position the stopcocks so as to divert the imaginary fluid running through them into various configurations. It was sort of a spatial configuration and visualization aptitude test. It wasn’t till later that I learned that this type of manifold was used as part of a monitor for arterial and venous blood pressures and to control IV fluids containing medications in patients. Apparently I passed her test because she hired me on the spot, probably more out of desperation than anything else. Her new department was performing a lot of specialized tasks in the hospital and they were very short handed.

When I showed up for work the next day, I still did not know what I was supposed to do. Shirley escorted me into the Hemodialysis Unit (what the hell is hemodialysis, I thought) and introduced me to Jerry Swett. Jerry was a well-groomed, soft spoken guy 14 years older than me. He was wearing a lab coat over surgical scrubs. I was still wearing my all white hospital-issued orderly uniform. He asked me about my background and then began to show me how to use an artificial kidney machine. By the end of the day I considered myself an expert (ahh, the arrogance of youth). During the day I asked him what he was. He didn’t look like an orderly, a med tech or even a doctor. Just what was he? He told me that “we” were Extracorporeal Technologists. He explained that an Extracorporeal Technologist was a person trained to operate equipment that used pumps to move blood in and out of patients for various purposes to keep them alive. Today we were pumping blood around to clean the patient’s blood whose kidneys were no longer working (so that’s what hemodialysis was). Tomorrow we would be pumping blood around to take over the function of the patient’s heart and lungs. Heart and lungs?!?! I sure as hell knew what those were and that I did not know anything about running a pump to perform that task. What had I gotten myself into? Jerry told me not to worry, he would teach me all I would need to know. And he kept his word. Over time, Jerry also taught me how to do ECGs, EEGs, operate the hyperbaric chamber, operate the Swenko organ preservation equipment that we used for kidney transplants and perform many other tasks as part of STS.

As the years went by I learned a lot about Jerry. He grew up in Montana on an Indian reservation and was an excellent horseman. He joined the service and became a Navy Corpsman in the Marines during the Korean War and was later stationed in Okinawa. While in the Far East, he picked up a liking for all things Japanese. He became an expert at jujitsu, a Japanese martial art used in close combat scenarios and became an official Marine Corps champion. He also developed a taste for Japanese cuisine, garb (kimonos) and culture (kabuki dancing and Kyudo, which is Japanese archery). He was wounded in Korea and eventually shipped back to the States for recovery. He wasn’t wounded badly enough to be discharged, so he was assigned to one of the large military hospitals. I don’t remember which one. It was there that he was taught how to run artificial kidney machines and heart/lung pumps. Somehow he eventually made his way to Kansas City after discharge, where he was hired to work in STS. While in KC he also taught martial arts classes professionally. In the 1970s the Kansas City Star newspaper would print an article about Jerry, calling him the “samurai perfusionist”.

Jerry always referred to the heart/lung pump as a “pump oxygenator”, which, I would later learn, was what Dr. Gibbon (the inventor of the heart lung machine) originally called his pump. He taught me how to operate blood pumps. I also learned to clean, re-assemble and steam sterilize a disc oxygenator, a venous/cardiotomy reservoir, heat exchanger and arterial filter. All of these were made of stainless steel and glass. They were sealed with rubber gaskets and held together with stainless steel tie rods. The tie rods were left loose while the devices were sterilized in the autoclave. Later when the devices were cool, we would tighten the tie rods with thumb screws. The rubber gaskets still often leaked, nonetheless. Before assembly and prior to sterilization, everything was sprayed on the inside with a silicone aerosol in an effort to reduce foaming. We put stainless steel sponges sprayed heavily with silicone in the venous/cardiotomy reservoirs to help stop foaming. But many times the foam would still build up and overflow the air vent of the reservoir.

Jerry knew how to operate all this high powered equipment and he taught me how as well. But the most important thing he taught me did not involve equipment. This was a time in American medical culture when doctors were treated like gods. And the most godly of them all were the heart surgeons. Nurses were expected to stand and give up their chair whenever a surgeon came on the floor or entered the operating room. (I am not kidding about this!)

1960s heart surgeon in consultation.

And if a nurse or any other paramedic were to offer advice to any doctor, they were considered uppity and disrespectful. It could even cost them their jobs if the doctor complained to the hospital administration. I remember one surgeon saying that any “monkey” could run a heart pump. This was an intentional insult from him, not a joke. But Jerry was a combat tested medic. He didn’t take disrespect or insults from anybody. He knew that the surgeons could not operate without him, no matter how much they demeaned the role of an “Extracorporeal Technologist”. Preparing, priming and operating a disc oxygenator circuit took great skill. None of the surgeons had a clue how it was done. Oh, sure, they had ‘run the pump’ somewhere at some point in their residency, but only under the guidance of a real Extracorporeal Technologist. Back then ‘see one, do one, teach one’ was a main stay and surgeons felt if they had seen a pump assembled, primed and operated once, they felt that was all they needed to know. Jerry didn’t take any guff from the surgeons. When Jerry spoke during the procedure he expected that the surgeons would listen and take him seriously. If not, Jerry would get their immediate attention with his best drill sergeant voice.

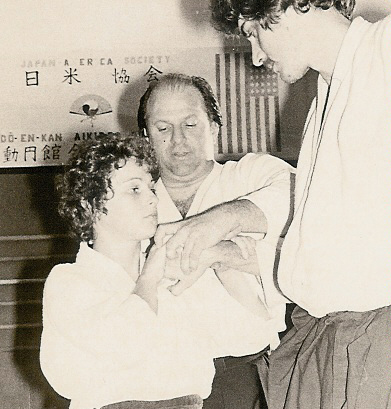

Jerry Swett in the 1970’s teaching marshal arts students. Jerry is in the middle.

Eventually Jerry moved on to other hospitals and I lost track of him in the 1970s. I later learned that he moved to his beloved orient, but eventually returned to the USA in the mid-1980s where he died in 1987 after a prolonged illness. He was only 52 years old. I never knew any of his relatives that I could contact nor could I find even an obituary for him. He was never listed in the ABCP roles as a CCP. I did manage to contact one of Jerry’s old martial arts students (Steve Scott) who was also inspired by Jerry. Steve became a martial arts instructor with a worldwide reputation in the profession. Steve supplied me with the only photo I have of Jerry, taken while teaching a martial arts student many years ago. While Steve and I had very different professions, we agreed that Jerry was our great teacher and mentor and that we shared a blessing in knowing Jerry.

12/15/17 Supplemental. On Dec. 8, 2017 I was contacted by Alan Sweeny after he came across this article while surfing the net. He said: “…I knew Jerry Swett and was with him at the end of life. He passed away on October 4, 1987 in Boise Idaho. Gary, I would be happy to share with you if you are interested.” I contacted Alan and we discussed our experiences with Jerry over the years. Jerry was born near Fort Benton, Montana. Alan told me that Jerry knew he was dying, but did not want any memorial service or even an obituary. Jerry was cremated and Alan scattered his ashes in Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness, a place Jerry loved to visit.

After his death The Jerry Swett Fund was established to provide short-term emergency assistance to clients for the costs of living expenses and essential transportation, but is not limited to them. The Jerry Swett Fund is not a publicly funded entitlement program. It is a discretionary fund administered as a community service by representatives of the Imperial Sovereign Gem court of Boise, Idaho. No federal, state, county, or contract funds are used for Jerry Swett Fund. One hundred percent of contributions to Jerry Swett Fund go to direct client services. No administrative, operating or personnel costs are charged to the fund.

Client Eligibility: In order to be eligible for assistance from the Jerry Swett Fund, individuals MUST meet the following minimum eligibility qualifications:

- Be HIV+ and living with HIV disease;

- Be a permanent resident of Idaho;

- Be in critical need of living expenses and essential transportation services not covered by existing Ryan White/Title II of Title III programs, private insurance, or other resources;

- Have a proven need for short-term financial assistance of living expenses and essential transportation services.

Enjoyed your story…remember making up our cannulas, using tubing and metal tips.

Cleaning metal heat exchangers.

Articles are always interesting…