Neonatal ECMO: My First Experience by Gary Grist RN CCP Retired

The first time I heard the word ‘ECMO’ was in 1985. Dr. Ron Howard MD, one of the pediatric surgeons, mentioned that he would like to have an ECMO program to support his congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients who frequently died after surgery. I had been a perfusionist at another hospital here in town in the late 60’s. We tried something akin to ECMO to support coding adult patients. Today we call it ECPR. We were unsuccessful; all those adult patients died. So, frankly, I was skeptical that ECMO would work. But, apparently, it did work in neonates. So, later that year we started to organize an ECMO program. Bonnie Butler and I were the perfusionists for Brian Keith MD, one of the heart surgeons, who had just become the co-director of new neonatal ECMO program along with Dr. Don Johnson MD, a neonatologist. We would be the 16th neonatal ECMO program to open in the USA. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Dr. B. T Barnham MD, the director of the nursery, who pushed hard for the ECMO program and convinced the staff neonatologists to become ECMO doctors.

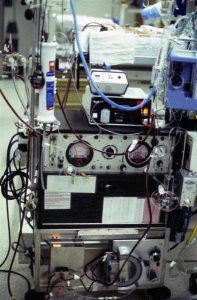

I remember Dr. Keith’s very detailed and specific orders: “Bonnie, Gary – ECMO – make it happen!” Our first task was to find some pumps. Since we didn’t have much money for capitol expenditures, this was a challenge. We visited my old friends at the adult hospital and talked them into selling us 3 old artificial kidney machines for $500 each. These old machines each had a blood pump, pressure monitoring, blood heating system, IV poles and wheels (so they could be moved around). What else could we possibly ask for?

Our first three ECMO pumps were modified artificial kidney machines as shown here.

We removed all the components that we wouldn’t need like the dialysate mixing equipment and rigged the machines to hold the oxygenator and mounted a sweep gas system on the IV poles. The special, extended use oxygenators were available commercially, but we had to build our own tubing sets from scratch. I spent hours cutting, gluing and assembling ECMO tubing packs, but only after I had completed many a full day’s work in the OR. We also designed our own neck cannulae made from chest tubes.

In the mean time, Dr. Johnson hired Barb Hershey RN in 1986 to be the ECMO Coordinator. Barb was an experienced neonatal nurse and had good organizational skills. She would need all her knowledge and skills for the task ahead. My job was simple; make an ECMO pump. Barb’s was immensely more difficult. First she needed to learn how to operate a heart/lung machine (which is what an ECMO pump really is) using me and Bonnie as an instructors. However, Bonnie and I did not know much more about how to use a pump for neonatal respiratory ECMO than Barb did. Then she needed to write procedures, produce educational materials, organize classes and train 30 nurses and doctors to be ECMO specialists (talk about herding cats). Remember that in 1986 there was no internet, no on-line resources and no computers. She visited other programs for training and got hard copies of their educational materials and procedures, but she wrote much of our material from scratch. She assembled an ‘ECMO Manual’ as a resource for training and problem solving; a tradition she has continued and updated for over 25 years.

Finally, we had our pumps, our team and our resources. It was time to start training. During 1986, we put a lamb on ECMO for 5 days (Monday – Friday) once every month of the year over at the nearby medical school animal lab. All the team members, nurses and doctors, sat 12 hour shifts around the clock. During those 5 days, Bonnie, Barb and I would routinely visit each shift, supposedly to see how they were doing. But our real purpose was to ‘sabotage’ the pump! We secretly turned off the oxygen, changed the sweep gas flow, changed the blood flow, kinked the blood lines, clamped off pressure monitors and carried out any other mischievous trick we could think of. Despite that, the teams solved those and many other problems that occurred without our duplicity. One night the circuit blew up, splattering everyone in the room with sheep blood; an unintentional but prophetic “ECMO Passover and Baptism” combined.

The early sheep did not do well. But, we learned a lot about using the ventilator during ECMO and how to keep the circuit from clotting (or blowing up!) with only partial heparinization and many other things. Most of all, we forged a team, bound by a common challenge; to keep infants alive who, without ECMO, would die. As we persisted, the lambs started to survive. Dr. Howard took a couple of the survivors to his rural home where they lived out their lives grazing in his front yard.

Then the day came in February 1987 when I met Dr. Johnson in the stairwell on his way to the nursery. With a big smile on his face he said “We have our first patient!” With that, this short, aging, balding, mild mannered, normally sedate Canadian neonatologist bounded up the staircase, leaping the stairs two steps at a time. You would have thought he was Bruce Jenner (the Olympian, before Caitlyn)! It is easy to understand his excitement. He had spent his whole career taking care of infants with lethal pulmonary diseases, often seeing them die no matter what he did; helpless to provide any additional intervention. Now he had a powerful new tool that he could use to cheat death. Unlike our first ECMO lamb, our first ECMO patient survived. So, after more than a year of intense planning, training and teambuilding, our ECMO program, like Don (Bruce Jenner) Johnson, was off and running in leaps and bounds.